HKCO

Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra Environmental, Social and Governance Artistic Director and Principal Conductor for Life Orchestra Members Council Advisors & Artistic Advisors Council Members Management Team Vacancy Contact Us (Tel: 3185 1600)

Concerts

Education

The HKCO Orchestral Academy Hong Kong Youth Zheng Ensemble Hong Kong Young Chinese Orchestra Music Courses Chinese Music Conducting 賽馬會中國音樂教育及推廣計劃 Chinese Music Talent Training Scheme HKJC Chinese Music 360 The International Drum Graded Exam

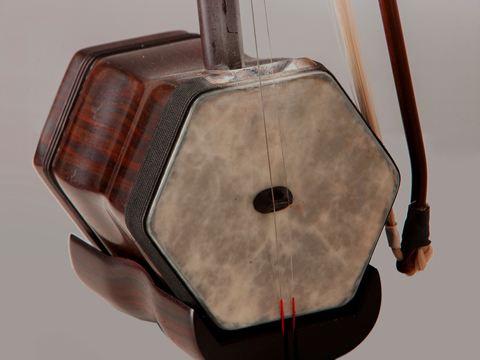

Instrument R&D

Eco-Huqins Chinese Instruments Standard Orchestra Instrument Range Chart and Page Format of the Full Score Configuration of the Orchestra

43rd Orchestral Season

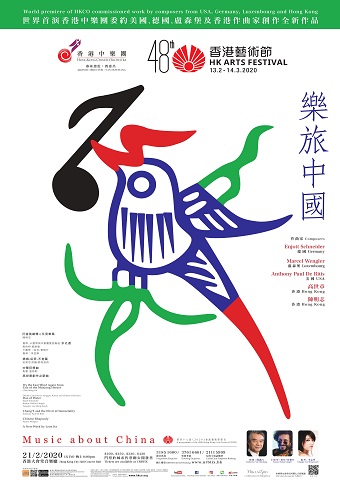

Music about China (Cancelled)

A programme of the 48th Hong Kong Arts Festival (2020)

Handpan: Sany Yan

Yangqin: Lee Meng-hsueh

‘Music about China - A programme of the 48th Hong Kong Arts Festival (2020)’ – Cancellation Notice

The Government has raised the "Preparedness and Response Plan for Novel Infectious Disease of Public Health Significance" to Emergency Response Level to reduce the risk of the spread of the novel coronavirus in the community. Also, due to the uncertainty of venue arrangements and the epidemic development, and out of concern for the health and well-being of the public, the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra announces that its ‘Music about China - A programme of the 48th Hong Kong Arts Festival (2020)’ concert, originally scheduled to be held at the Hong Kong City Hall Concert Hall on 21 February, 2020, has been cancelled. Ticket(s) holders can complete the form and choose the following arrangement and return it to the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra with the original ticket(s) on or before 30 April 2020.

Ticket arrangement:

1. Apply for a full refund (of the face value of the ticket, by cheque or cash)

2. Donation to the ‘Music For Love’ Scheme.

Allowing students, underprivileged groups and families the opportunity to share the beauty of Chinese music in a live setting. We are certain that experiences like this would enable them to widen their vistas in the arts and develop an interest in Chinese culture.

(Donations of HK$100 or above are tax deductible with official receipt.)

Enquiries: 3185 1647/keithyeung@hkco.org

HKCO Office: 7/F, Sheung Wan Municipal Services Building, 345 Queen's Road Central, Hong Kong (Marketing and Development Department)

Working hours: Monday to Friday (10:00am-12:30pm / 2:00pm-6:00pm)

*Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance Statement:

The personal data that you supply will be used for the communication, contacts and the promotion of latest information, programmes, events, discount and offers through the above stated channels. You can make subsequent changes on your choice of receiving further information (including direct marketing materials) by sending a written unsubscribe request to the following address or contact the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra as stated below:

Address: 7/F., Sheung Wan Municipal Services Building, 345 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong

Tel.: 3185 1600 | Fax: 2815 5615 | E-mail: inquiries@hkco.org | Website: www.hkco.org

It’s the East Wind Again from Tale of the Mahjong Heroes Chan Ming-chi (Commissioned by the HKCO / World Premiere)

The first movement: The strategic battle for the winning tile

The second movement: When luck comes in full circle

The third movement: For the myriad living things on earth

The fourth movement: A symphony of clattering tiles

Handpan: Sany Yan

Chang’E and the Elixir of Immortality Anthony Paul De Ritis (Commissioned by the HKCO / World Premiere)

Chinese Rhapsody Marcel Wengler (Commissioned by the HKCO / World Premiere)

Double Concerto for Yangqin, Kanun and Chinese Orchestra Dao of Water Enjott Schneider (Commissioned by the HKCO / World Premiere)

The first movement: “Supreme Good is Like Water” (Lao Tse, Dao De Jing)

The second movement: Garden with Glittering Fountains

The third movement: Buddha Mind – the Hidden Power of Lowest Places

The fourth movement: Reflection of the Moon on the Water (Variations)

The fifth movement: Power, the Shape of Water

Kanun: Hakan Güngör

Yangqin: Lee Meng-hsueh

Blue Notes Leon Ko (Commissioned by the HKCO / World Premiere)

It’s the East Wind Again from Tale of the Mahjong Heroes Chan Ming-chi (Commissioned by the HKCO / World Premiere)

Mahjong is considered the quintessential recreational game in Chinese gambling culture. It makes references to the Chinese theory of the Five Elements, the ultimate concept of “Three creates all things” set out in the Book of Changes, and even divination works such as Qimen Dunjia.

A set of mahjong tiles has three suits: Circles, Bamboo and Characters. The bamboo suit represents heaven; the circle suit, earth; and the character suit, written using the Chinese character for “myriad”, the myriads of living beings and the potentiality for change in Buddhism. Mahjong is a game of strategy, calculation, and techniques. There are all kinds of ways to go about the game, and the competitiveness means that only players who can make quick judgments and devise winning strategies can become the best of the best.

The work is in four movements, each featuring signatory sounds played by different instruments. Longitudinal, end-blown bamboo instruments such as the chiba (the Japanese Shakuhachi) represent the Bamboo suit, handpans and other round-shaped instruments symbolize the Circles suit, and the muyu (wood block) and vocal chorus represent the Characters suit. The finale is a symphony of all three groups. The recurrent “dong dong dong” signify the beginning of another four-rounds, with the East Wind as the first. (The “dong” sound is a homophone for the Chinese character of “east”). Each appearance of “dong dong dong” establishes the tonic for the overall tonality of the piece.

The first movement: The strategic battle for the winning tile

The mahjong game starts: like hunters advancing toward their prey, the players come up with all kinds of strategies and battle it out on the mahjong table. The chiba opens the movement with its explosive breath attack (mura iki) notes and aggressive, and powerful timbre. The target of all “mahjong heroes” is to assemble a hand and wait for the clamp down with the winning tile to end the game.

The second movement: When luck comes in full circle

Each game of mahjong proceeds in an unpredictable manner. Time and time again, players find themselves with a good hand, but struggle to take a win, just like the handpan’s droning and throbbing in its limited acoustic range. Just when it seems like there is no hope, the God of Wealth bestows his blessings, and the resulting sense of triumph burns like a fire in the soul.

The third movement: For the myriad living things on earth

The game of mahjong is about assembling a winning hand. A single tile can turn the tide, while players can switch to a different suit mid-game and seize the initiative. As the lyrics from the theme song of Games Gamblers Play go, “there is no need to be mad if you lose everything”, the cyclic figure suggests that be it a good hand or bad, a mahjong hero should always keep his cool.

The fourth movement: A symphony of clattering tiles

There are two sides to all things. Whether one considers mahjong as a form of gambling or entertainment, the fact is that it is a way of life that subtly reflects the characteristics of different local cultures. At the end of the day, we are free to savour in the delights that the game brings to our hands, brain, ears and eyes. As for finding life’s meanings and wisdoms in the symphony of the clattering of tiles, it is up to the individual.

* The exotic instruments used in this piece: Blue Dragon (East / Blue Green), White Tiger (West / White), Red Phoenix (South / Red), Black Turtle (North / Black), handpan, water drum and African maracas.

Double Concerto for Yangqin, Kanun and Chinese Orchestra Dao of Water Enjott Schneider (Commissioned by the HKCO / World Premiere)

The first movement: “Supreme Good is Like Water” (Lao Tse, Dao De Jing)The second movement: Garden with Glittering Fountains

The third movement: Buddha Mind – the Hidden Power of Lowest Places

The fourth movement: Reflection of the Moon on the Water (Variations)

The fifth movement: Power, the Shape of Water

Water is an important metaphor in Dao De Jing to explain the deep meaning of Dao. Lao Tse’s statement “Supreme good is like water” (Chapter 8) opens the doors to central aspects “of the right way”: weak and soft is getting to hard and strong, water is the essence of “proper way-making” because water is the element of the lowest places. The famous Chinese tune Reflection of the Moon on the Water is the base of variations in fifth movement and leads to the mightiness of Xi Jiang. – The orchestration of this composition is a deep symbol for the ambivalence of the element “water”: the two soloists with their sensitive and subtle soundscape are representing the weakness, and the full orchestra is representing the power of the Dao.

This work is dedicated for Maestro Yan Huichang in friendship and in great admiration of his never-ending work for international understanding and peace.

Chang’E and the Elixir of Immortality was composed from October through December 2019, expressly for the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra. This work comes upon the success of De Ritis’s Percussion Concerto

featuring Chinese Percussion and Western Orchestra in April 2018, titled The Legend of Cowherd and Weaver Girl; and is written 15 years after De Ritis’s first work for Chinese orchestra, his concerto for pipa, titled Ping-Pong (2004), written for the Taipei Chinese Orchestra, featuring pipa virtuoso, Min Xiao-Fen.

Like much Chinese traditional folklore, there are several versions; this composition is modeled after the

following interpretation…

Chang’E and the Elixir of Immortality begins with the earth barren and oppressed under the heat of ten suns, depicted by soft and slow moving sound clusters in the highest registers of the bowed strings. The human suffering continues until we hear a theme of hope in the solo zheng, soon followed by rhythmic and masculine gestures by the plucked strings representing HouYi. Soon, our hero begins shooting down nine of the ten suns with his mighty bow and arrows, a series of nine massive glissandi in the bowed strings followed by percussion crashes. The people cherish HouYi as their hero with a fanfare led by the suonas — and soon after HouYi meets and falls in love with Chang’E, depicted with a slow dance of courtship featuring dizi and daruan. Yunluo signify the arrival of the Goddess who offers HouYi the Elixir of Immortality for his heroism. Romantic and regal music soon yields to the double-crossing Peng Meng, HouYi’s jealous apprentice, who learns of and seeks the Elixir of Immortality for himself. He confronts Chang’E and demands the elixir from her — and in a fleeting moment, she drinks the elixir herself rather than hand it over to Peng Meng. The powerful elixir soon takes its effect as the music transforms from magic, to reflections of hope and love, and finally to a long ascending passage that reaches higher and higher pitches — Chang’E rising to the moon, where she will live forever. When HouYi returns from the hunt, he learns of Chang’E’s fate, and is overcome with grief and sadness – he sees Chang’E’s shadow in the moon. The composition concludes with a brief postlude harkening back to the musical gestures of hope embodied by HouYi and his heroism, and Chang’E rising to the moon —and one can envision HouYi setting out fruits as offerings to Chang’E as an expression of his eternal love.

Chinese Rhapsody Marcel Wengler (Commissioned by the HKCO / World Premiere)

The multiple impressions I gained during my countless trips to China have inspired me to compose this piece. Be it the grand landscapes, the outstanding modern architecture, the bubbling life in the cities, traditional events such as the ceremonies in the Chinese temples, the horse races in Hong Kong, or the daily Tai Chi exercises in the city parks, all these are recollected in my Chinese Rhapsody. On the other hand, I have tried to emphasize the traditional Chinese instruments of the orchestra through my orchestration.

This composition is dedicated to the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra and its outstanding Artistic Director and Conductor Yan Huichang.

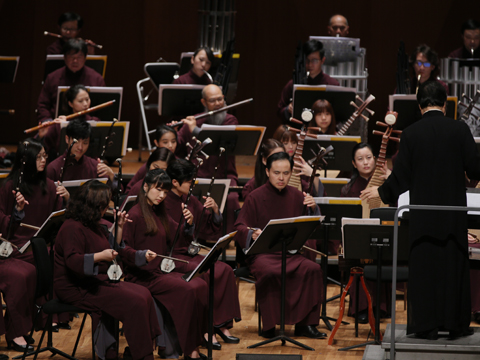

Music about China - Telling Chinese Stories to the World

As we enter the third decade of the millennium, the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra’s ‘Music about China’ series has also adapted to the global trends. Out of the five new works in the programme, two are newly written by Hong Kong composers, and three are by overseas composers commissioned specifically for this concert.

Are the non-Chinese capable of telling stories about China?

To answer this question, we have to return to something that has been brought up time and time again – the question of defining “Chinese music”. As early as the 1970s and 1980s, Doming Lam, who is known as the “Father of Hong Kong Modern Music”, borrowed contemporary American composer Aaron Copland’s maxim that “American music is whatever is written by American composers” and argued that “Chinese music is whatever is written by Chinese composers”. As far as definitions go, this is short and to the point, but further elaboration is needed. Being “Chinese” is not defined as being a Chinese by descent or by nationality. Rather, it refers to the cultural identity of being a Chinese – a person who is not necessarily Chinese by descent or by nationality, but who shows a deep understanding and love of Chinese culture. It also means the composer has to have made a genuine effort to compose a piece of Chinese music. Lam once “composed” a piece that was accepted by his advertising client, who thought of it as a Baroque piece. This was because he wanted to compose a piece in Baroque style. As he made no effort in making it a piece of Chinese music, it obviously would not be deemed “Chinese music”.

As such, Lam's definition of “Chinese music” provides a way of thinking that answers the question of whether non-Chinese persons are capable of composing Chinese music and telling stories about China. First, we have to consider their understanding of Chinese culture, and whether or not they are culturally assimilated.

Five different subjects on China

The subject matter chosen by the five commissioned composers of this concert is all related to the everyday life and traditional culture of the Chinese, but each is different in its own way. In It’s the East Wind Again from Tale of the Mahjong Heroes by Hong Kong composer Chan Ming-chi, the ‘national’ game of Mahjong is a faceted mirror of the ways of the world. Another new original composition is by Leon Ko, also from Hong Kong, called Blue Notes. The title has two-pronged meaning: the original Chinese laam yum is a homophone of naam yum (or nanyin in pinyin), a singing genre of South China used to be performed by blind, itinerant singers. The genre has been revived in Hong Kong in recent years and grown in popularity not only as a standalone show but also as part of the sung repertoire in Cantonese Opera productions. The English title also immediately calls to mind the genre of ‘blues’ in Western music, and has similar functions as expressions of sadness for those who have suffered hardships in life.

As for the works by the three non-Chinese composers, Enjott Schneider’s double concerto Dao of Water for yangqin, kanun and Chinese orchestra is, as the title of the first movement clearly shows, derived from the concept that “supreme good is like water” from Laozi’s Dao De Jing; that the key concept of “Dao” (the Way) is the weak and soft can become strong and hard. The titles of the following four movements – Garden with Glittering Fountains, Buddha Mind – the Hidden Power of Lowest Places, Reflection of the Moon on the Water (Variations) and Power, the shape of Water – are also related to this central idea. Chang'E and the Elixir of Immortality by Anthony Paul De Ritis is a musical retelling of the Chinese folklore Chang'e Ascends to the Moon, while Chinese Rhapsody by Marcel Wengler is composed based on his impressions derived from what he saw and heard during his many trips to China, including Hong Kong.

Bringing in a global perspective for audience validation

So there is no doubt that all five composers are telling stories about China through their music: they all have a reasonable understanding of Chinese culture, including the three non-Chinese who have stayed or lived on Chinese soil for some time. Some have even had compositional experience with works on Chinese themes. In accepting the commission to write for this concert, they would naturally strive to add new works to the Chinese music repertoire. Yet, no matter where they come from, whether their efforts are successful, and whether their Chinese stories can reach out to the hearts of the listeners, it needs to be played and to be heard. The audience’s validation is a crucial footnote to the argument that “Chinese music is whatever is written by Chinese composers”.

Whatever the case may be, composers from China and Hong Kong have long been able to tell all sorts of human stories through their music in today’s globalized world, and their non-Chinese colleagues are joining the league with musical stories about China. This 2020 edition of ‘Music about China’ is clear in its intentions to bring in a global perspective to the telling of stories about China. As we welcome the Year of the Mouse, let us work hard at broadening the perspectives for those on stage and those in the arena.

Your Support

Friends of HKCO

Copyright © 2026 HKCO